Monthly Archive for May, 2013

In Italy there is still a craftsmanship conception of high-level sport particularly true in individual sports. In most cases, the development and success of an athlete is based on a deep collaborative relationship with his/her coach. It is not uncommon that the coach is the husband of the athlete or the parent (father/mother). It’s obvious that this system is subject to all interference that are typical of the dual relationships. The psychological components of each of these relationships have unbelievable significance, because the training is to build situations with predetermined levels of stress that the athlete must successfully deal to improve in his/her performances. In this context, the coaches have a reduced exchange of ideas and discussion with other colleagues and the use of innovations produced by the sports science depends only on their curiosity and desire to upgrade. The limitation of this approach lies not only in the limited use of the contributions of science by the coaches but also the failure of researchers to listen and understand what are the needs and demands of the coaches. In other words, there is need to talk together, to share ideas, to criticize each other in a constructive way and to build work plans based on collaboration.

Words and ideas to think about.

“Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

(From Ulysses by Alfred Tennyson)

Great publication with a lot statistic data regarding the 60 years from the Everest conquest on: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/interactive/2013/may/28/everest-60-years-mountaineering-interactive?CMP=twt_gu and http://www.guardian.co.uk/travel/gallery/2013/may/23/mount-everest-first-successful-ascent-in-pictures?picture=409252599#/?picture=409252588&index=16

By Steve Myall

Daughter of physiologist who helped Sir Edmund Hillary and Nepalese Sherpa Tenzing Norgay to conquer Everest reveals extraordinary story of survival.

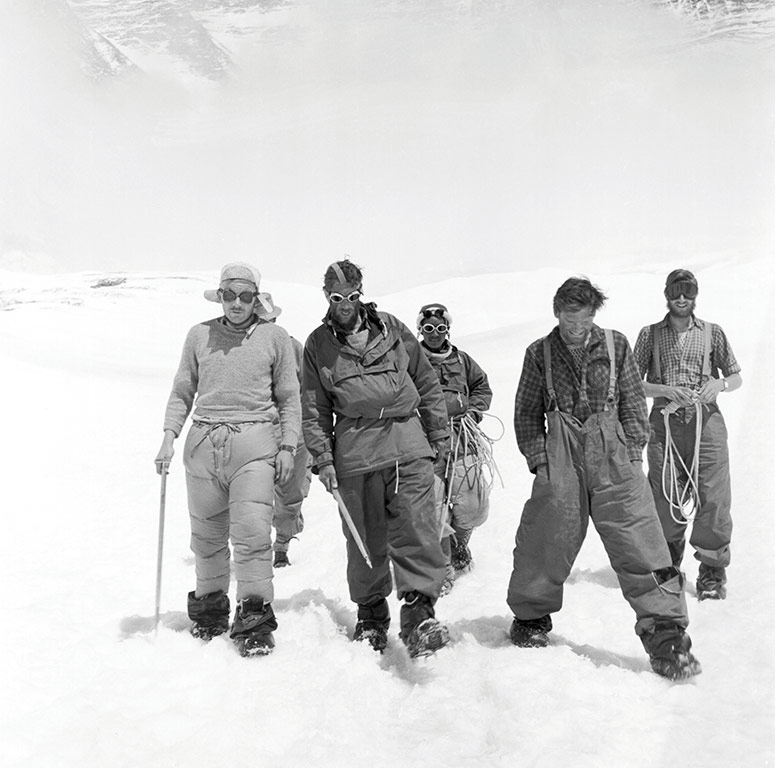

British Expedition: Physiologist Griff Pugh (circled) with the team in May 1953.

But 60 years ago, on the eve of the Coronation, news came through that delighted the whole of Britain – Sir Edmund Hillary and Nepalese Sherpa Tenzing Norgay had, finally, reached the snowy peak of the world’s highest mountain.

It was an amazing achievement by undoubtedly brave men. But why did they succeed where so many had failed?

One reason has, until now, remained hidden to history. The success of Sir Edmund and his team was, in fact, due to the work of a man who himself never reached the summit.

He was Griff Pugh, the physiologist on the trip. His daughter, Harriet Tuckey spent eight years researching the expedition and her father’s role in it. Here she reveals how the greatest achievement in mountaineering came to pass.

Between 1921 and World War Two seven major British expeditions had tried to scale Everest… and failed.

Although six men reached 28,000ft (8,500m) in 1924 – a thousand feet below the summit – they were unable to climb higher.

There were two reasons for their difficulties. The first was that Britain then controlled and restricted access to the mountain.

This meant our climbers faced no competition and, extraordinary though it may seem by today’s standards, they believed aids such as bottled oxygen were “unBritish” and “unsporting”.

Traditionally Everest had always been climbed from the north, through Tibet, as it was thought there was no climbable route up the mountain from Nepal.

But in 1951 – after Western climbers were stopped from using Tibet by its Chinese occupiers – a British climbing team found a way up via Nepal.

They applied for permission to use that way the next year but, to their horror, found the Swiss had already had a crack at the climb, getting further up than anyone before them.

Unlike the British, the Swiss team had consulted specialist physiologists and used purpose-built oxygen equipment.

The worried British got permission to climb in 1953 knowing the French planned a similar expedition in 1954, and the Swiss another in 1955.

They then sent a training expedition to the Nepalese mountain of Cho Oyu to test the theories of Pugh, who said the appliance of science would make the crucial difference.

At the dizzying heights near Everest’s summit the air is thin and breathing is difficult.

But while oxygen equipment for climbers had been available since 1922, in the years before their successful attempt, the British considered artificial aids “unethical”.

The majority of climbers also feared the weight of the apparatus cancelled out any potential benefits.

Oxygen was not the only problem. Everest climbers were terribly afflicted by cold and thought some frostbite was unavoidable.

Climbers also suffered from extreme exhaustion, disturbed breathing, headaches, loss of appetite, rapid weight loss, sleeplessness, persistent coughing, sore throats and stomach problems. All these sapped their strength, undermining their chances of success.

They were unable to recover from fatigue and their strength was further undermined by extreme dehydration which they did not understand.

Climbing teams returned from high altitude thin and haggard – mere ghosts of their former selves.

There was also the problem of diet. Climbers at high altitude lost their appetites and suffered drastic weight-loss and stomach upsets.

Time and again, the strongest men were stopped in their tracks long before they could reach the summit of Everest, or indeed the summit of any of the 10 highest mountains in the world. It was these problems that needed to be solved before anyone would reach the top.

In 1952 on Cho Oyu little changed in the British approach.

The team was led by experienced but disorganised Eric Shipton who doubted Griff Pugh’s theories on acclimatisation and oxygen use.

But the next year he was replaced by Army officer John Hunt, who was known for his excellent organisational abilities – and Pugh was given the freedom to get to work his own way.

His four-week programme of acclimatisation and lessons in oxygen use ensured the men were better prepared and fitter than any previous team.

He told the climbers how much to drink, made their stoves more efficient and worked out how much fuel would be needed to melt snow for drinking water.

Pugh improved the food too, after first working out the energy costs of carrying it.

He then came up with complex dietary principles for high-altitude climbing – which included special treats – which are still followed today.

To top it all, he designed high-altitude boots and wind-proof suits, modified the snow goggles, tents and sleeping bags – and designed special air beds for sleeping on.

As with all high altitude climbs, the men had a series of camps.

Hillary and Tenzing spent the night before their summit assault sheltering in their “high ridge camp” in a tent made of the fabric chosen by Pugh.

They started up their cooker (made to Pugh’s specifications) and finding it “worked like a charm” brewed “large amounts of lemon juice and sugar”.

After a “satisfying meal out of our store of delicacies” – from the special high-altitude ration boxes devised by Pugh – they retired for the night using sleeping oxygen (under the expert’s oxygen policy), resting on air mattresses also developed specially.

After getting up at 4am they brewed still more sweetened lemonade because Pugh had told them that being dehydrated was the biggest threat to their ability to keep going.

Then they set off and, thanks to Pugh’s work and their level of fitness, found the final climb took only five hours. In fact, they returned from their historic mission in far better condition than any previous Everest assault pair.

Hillary and Tenzing got all the glory. But their magnificent achievement was also a huge success for Pugh. It showed that his ideas really worked.

Despite this, his diary contains only the simple entry: “2pm. Hillary and Tenzing arrive back in camp from the south col after successful ascent of Everest”.

Despite the huge role played by Pugh, his contribution was not made public. Team leader Hunt said: “It’s men who climb mountains, not equipment.” A romantic tale of heroism and adventure was far more interesting to people than advances in science and technology.

But in the climbing community, Pugh’s innovations were immediately studied and copied.

Within three years, the world’s six highest mountains had all been climbed in relative safety.

Within five years, only two peaks above 8,000m remained and one proved completely inaccessible.

Pugh’s later work in hypothermia led to the creation of much of the lightweight outdoor clothes used today.

And his studies into the effects of altitude on the human body still influence professional athletes.

But while climbers often talk about this extraordinarily period in Himalayan climbing many are still blind to Pugh’s achievements, attributing the successes to a sudden blossoming of skill, courage and fortitude.

But Sir Edmund Hillary knew Pugh’s worth. In an interview shortly before he died in 2008 he told Harriet: “Your father, he, in a way, made it possible for us to climb Everest.”

From: http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/secrets-behind-conquering-everest-60-1911119

By: Cedric Arijs

When the European federation of sport psychology announced its conference with the working title, ‘Development of expertise and excellence in applied sport psychology’ I had the feeling this 2-day conference would be enriching for a young sport psychology student like myself, and I was not disappointed! Allow me to share some insights.

The many experienced applied sport psychologists (APSs) and researchers didn’t give the recipe for a successful career on a silver platter. But why would there be a clear-cut trajectory in a discipline where the answer is so often “It depends…”? Therefore, self-reflection and peer discussions are necessary. During the weekend I met many (future) colleagues in the field who were more than willing to share their stories with me. And I guess there are worse places for networking and becoming acquainted than a nice boat dinner on the Seine River next to the Eiffel Tower, wouldn’t you agree?

Read more on http://emsepblog.tumblr.com/post/51137951759/reflections-of-the-2013-fepsac-conference-in-paris

Learning new psychological skills to improve the performances is not difficult indeed it is quite easy. Despite more and more athletes embark on the road of mental training, many drop out after a short period, while continuing to think they’d like to be more confident, more focused, more tough and so on. This is because many think that the psychological preparation is something that it could be learn in a few months (a few anyway) and then in a spontaneous manner when you go in competition you will be mentally ready. In fact, many athletes have difficulty understanding the psychological preparation to the race is a real form of training and as with the physical and technical training who continue for ever the same applies to the mental. It means the athlete should strive to improve mentally every day that is dedicated to the sport, there can be no shortcuts.

For an athlete who in his career has reached the absolute top, be in a position of having to go back to work on his technique and on a different race management, because the rules of his sport have been changed is not an easy task. Especially if it happens in the post-Olympic period in which the majority of athletes tend to take some time to recover from the Olimpic stress. The combination of these aspects, rules changes and the need to maintain the commitment at the highest level, can lead to a condition of mental stress in which the athlete would not want to be in this stage of his career. In addition, the young athletes of the same sport perceive the post-Olympic period as an opportunity to gain experiences at the international level and therefore they are motivated to make every effort to be noticed by the national coach. There are so many reasons that prevent from living this year so undemanding but instead push in the direction of a fastf adaptation to new technical rules and competition changes.

Learn how to handle stress on the tennis court – and in life – in a fast and easy way with the technique of “Centering” and knowing your “Personal Attentional Style.” This World of Tennis Italy new “crash course” offers explanations and a simple and rapid technique to handle stressful situations.

Use of the tennis court, in other sports and in everyday life: the results will amaze you.