For sports psychologists, the study of the cognitive strategies of long-distance runners is particularly interesting, as these athletes undergo extremely high psychophysical stress during which they must perform at their best.

The first systematic study conducted on the cognitive strategies of long-distance runners was carried out by Morgan and Pollock [1977], with a sample consisting of world-class athletes and lower-level middle-distance runners. To classify the strategies used during running, the authors used the terms association and dissociation.

In the first condition, athletes focus on sensations coming from their bodies and are aware of the fundamental physical factors for that type of performance. In the dissociation strategy, on the other hand, the athlete’s thoughts are concentrated on anything other than bodily sensations.

During competition, the cognitive strategies of the elite group differ from those of the other group based on these two characteristics. In fact, to counteract painful stimuli, lower-level athletes use the dissociative strategy, while elite athletes use the associative one and consequently modulate their pace.

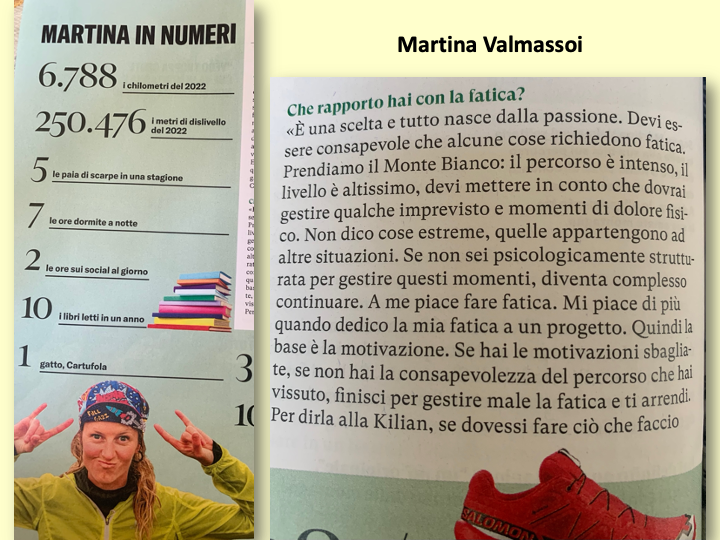

Moreover, experienced marathon runners do not attribute much importance to the so-called pain zone, for at least two reasons that differentiate them from less experienced runners. The first refers to their physiological superiority, which allows them to run at their limit with less difficulty. The second involves the fact that they avoid this pain zone because they can self-regulate throughout the entire race based on their internal sensations.

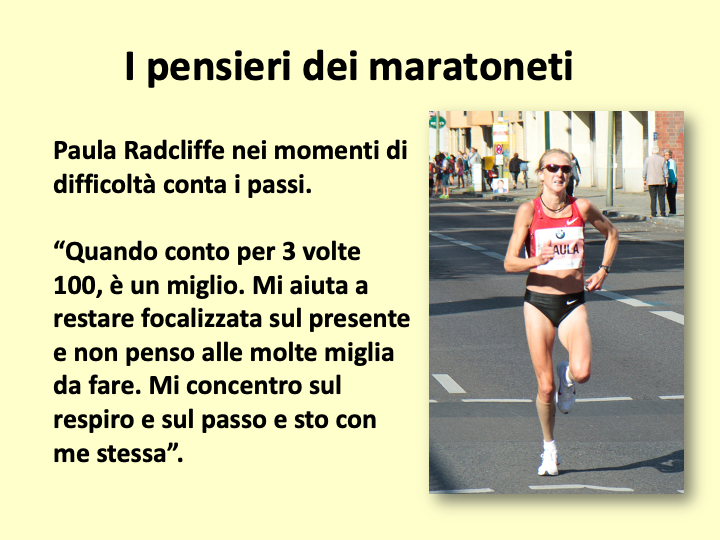

Specifically, in the associative phase, the runner, in an effort to maximize performance and minimize discomfort or painful sensations, continuously focuses on physical sensations such as breathing, temperature, the heaviness of calves and thighs, and abdominal sensations. This cognitive mode is quite demanding for athletes, as it requires the ability to concentrate for extended periods. The dissociative phase occurs when the athlete voluntarily distracts themselves from the sensory feedback continuously received from the body.

In summary:

Association and dissociation should be considered as the two extreme poles of a continuum and not interpreted in dichotomous terms, especially when used in long-distance races.

- The use of associative strategies is more strongly correlated with fast long-distance performances than the use of dissociative strategies.

- In races, runners prefer to use associative strategies (focusing on monitoring body processes and controlling race strategy).

- In training, however, they tend to use dissociative strategies more, although both strategies are still used in both contexts.

- Dissociation is inversely correlated with physiological awareness and feelings derived from the perception of exertion intensity, as highlighted in laboratory studies.

- Dissociation does not increase the likelihood of injury and can reduce the fatigue and monotony of running and recreational races.

- Association can allow the athlete to continue competing even in the presence of sensory pain.

- Dissociation should be used as a training technique by those looking to increase their exercise adherence, as it allows for a better and more enjoyable perception of the end of the exercise.

- As training load increases, there is a shift from dissociative strategies to associative strategies to increase the athlete’s concentration on the task at hand.

- When using mindful focus on oneself to enhance running efficiency, attention should be directed toward bodily sensations rather than automatic responses such as breathing and running movements.