Tag Archive for 'sport'

In sports, we find ourselves in the curious situation where its importance is demonstrated in leading a physically active lifestyle, reducing daily stress, and promoting individual well-being. On the other hand, for athletes, sports can be a source of stress, trigger psychopathologies, and distance them from the reality of everyday life.

We have athletes like English footballer Henderson, who moved to play in Saudi Arabia for 40 million and now considers himself discontented and wanting to leave, and others who consider themselves happy because they have managed to overcome the battle against sedentary lifestyle and its daily limitations.

What do we learn from these situations? That sports don’t always bring the good they are often rhetorically claimed to provide. Sport, like studying and working, is a human activity, and its positive/negative effect on a person depends on how this activity is carried out.

Recreational sports are undertaken based on the choice to take care of oneself, as a leisure activity, enjoyable and personalized. On these foundations, it’s a journey that, through movement, generates well-being and the development of new skills over time.

Performance sports, on the other hand, require total commitment from those who choose them, and competitions represent moments to compare one’s skills with those of other athletes. Absolute-level performance sports demand total dedication, just like any other human activity that a person considers fundamental to their self-realization. It’s an activity for which one decides to abandon other activities perceived as obstacles to the all-encompassing commitment to the sport. In my opinion, it’s the best athletes with high expectations who may develop serious psychological problems, while those with less success or who do not want to engage in such demanding activity tend to create other situations in their lives that, inadvertently, protect them from these issues.

The alarming issue for me is that these problems are not only common among top-level athletes but also among adolescent athletes. These are 14-19-year-old boys and girls or even younger if we talk about early development sports, who, due to their abilities, have entered a federal or organizational sports circuit engaging in highly demanding activities as athletes, with the goal of turning it into their profession but unsure if they will succeed.

What do we, who work with them, want for them? Should they pursue the activity like the seniors to see who will succeed? Should they attend specialized schools to train and compete for longer? What is the role of families? There are many questions, and I believe we have few answers at the moment.

If you are interested in learning more about the role of sports in patients with multiple sclerosis, you can read this summary article on this topic.

Donze, Cecile1; Massot, Caroline MD1; Hautecoeur, Patrick2; Cattoir-Vue, Helene1; Guyot, Marc-Alexandre1. The Practice of Sport in Multiple Sclerosis: Update. Current Sports Medicine Reports 16(4):p 274-279, 7/8 2017.

The practice of sport by multiple sclerosis patients has long been controversial. Recent studies, however, show that both sport and physical activity are essential for these patients. Indeed, they help to cope with the effects of multiple sclerosis, such as fatigue, reduced endurance, loss of muscle mass, and reduction of muscle strength. The beneficial effects of physical activity on these patients have been underlined in several studies, whereas those of practicing sport have been the subject of fewer evaluations and assessments. The aim of this update is to report on the effects of sport on multiple sclerosis patients. The benefits of sport have been demonstrated in several studies. It helps multiple sclerosis patients to increase their balance, resistance to fatigue, mobility and quality of life. Several biases in these studies do not enable us to recommend the practice of some of these sports on a routine basis.

Since many years sports have been completely privatized f; it is now rare for young people to play spontaneously on their own in parks and gardens. Sports has become one of the household expenditure items. I am not aware of the costs of sports after the pandemic and whether they have increased/reduced. However, we have data from the immediately preceding years.

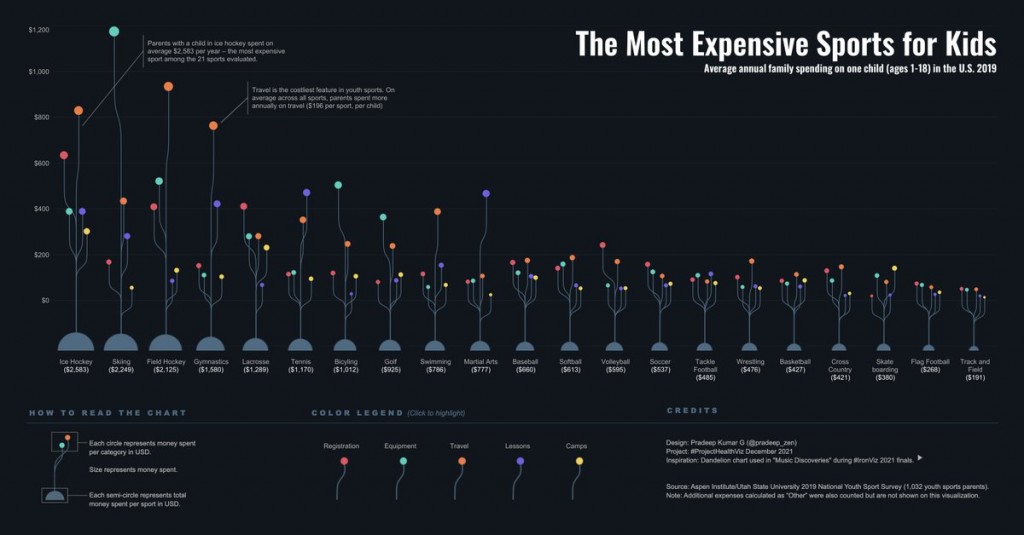

This table on a survey conducted in the U.S. shows that the most expensive sports are ice hockey (US$2,583 annually) , skiing US$2,249), field field hockey (US$2,125), gymnastics (US$1,580), lacrosse (US$1289) and tennis (US$1,170). It is striking that golf is between cycling and swimming. Not surprisingly, the cheapest sport is athletics. However, it is likely that costs vary from nation to nation. Also, this survey does not include horseback riding, a particularly expensive sport.

These data are relatively different from those in Italy.

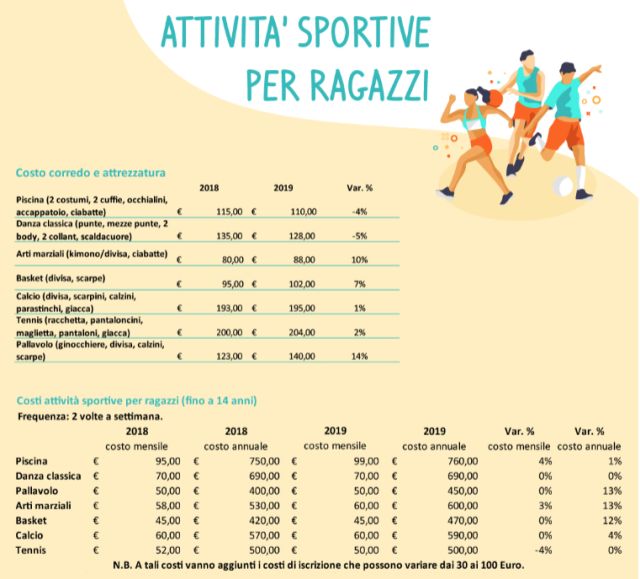

The Federconsumatori National Observatory has monitored the costs of various courses (including swimming, tennis, basketball, soccer): the costs of sports activities for children (up to 14 years of age) as well as the cost of the kit and equipment needed to attend some sports activities (such as uniforms, sneakers, etc.) as shown in the table below. The limitation here again as in the U.S. survey is that it covers the years prior to the pandemic and gives no indication of what kind of adjustment led to the long-term closure of sports centers, or how much we suffered e.g. swimming pools compared to tennis clubs, which were the first to be able to restart.

To these costs must be added registration fees, which, depending on the sports center chosen, can range on average from 30 to 80 euros. “Definitely excessive costs that, in addition to weighing on Italians’ expenses, can push them toward not practicing sports activities, which are fundamental for the health and education of children,” – argues Emilio Viafora, President of Federconsumatori.

In fact, swimming courses, warmly recommended by all doctors, especially with regard to the growth and development of children and young people, have touched rather high costs, definitely excessive if one considers in the household the presence of several children. The cost of a swimming course turns out to be 720 euros annually, to which must be added 115 euros for equipment and about 55 euros for registration, for a total of 890 euros. Even more expensive is the choice to practice ballet, with a cost of 690 euros per year, to which 140 euros must be added for equipment, 110 euros for the end-of-year recital and about 55 euros for registration, for a total of 995 euros per year.

By contrast, the cheapest sport turns out to be basketball, which costs 508 euros annually, including 420 euros for the course, 83 euros for equipment and about 55 euros for registration. To meet these costs, several families are forced to take out loans from financial institutions, generally finding themselves having to repay the entire capital required in 12 months.

How sport has evolved.

- The age of top athletes has decreased; in women’s tennis there are 15 Under 22 among the top 100.

- The number of States promoting their athletes has greatly increased, from countries of the former Soviet Union to Arab countries to those on other Continents.

- For many families, sports careers have become a realistic opportunity for their children to pursue.

- There is no longer spontaneous sport run by young people independently but has been totally privatized on most Continents.

- In many sports from the age of 14/15 years, frequent and selective competitive activity begins.

- Worldwide, the number of competitions has increased dramatically, and people compete 11 months of the year.

- By age 16, athletes, girls and boys, are also training 25 hours a week for at least 45 weeks.

- Most athletes follow a program not only of technical-tactical but also of specific and advanced mental and physical training.

- Women’s sports are gaining similar relevance to men’s sports, and mixed teams have been introduced in the Olympics, where gender parity has almost been achieved.

- This type of sports development results in athletes experiencing stress and often debilitating psychological problems generated by always having to show their value. At the same time it is a source of frustration for those who are excluded from this climb to success.

The phenomenon of cheating has been particularly investigated in the business world. The reasons that lead to financial fraud have been investigated, Three broad and different categories have been identified: conditions, organization structure, and choice, and they can also be applied to this particular type of fraud that is doping.

The first condition, concerns motivations and pressures to use the fraud. Pressure on the company to achieve its intended goals plays an important role in taking this route. In this situation, executives deliberately commit illegal actions to deceive investors and creditors in relation to poor or unfavorable financial performance. In the world of sports, the need to achieve results at any cost and the pressures exerted on athletes to do so represent situations similar to those highlighted in the world of finance, not the least of which relate to the possibility of seeing one’s compensation rise by virtue of sporting success.

The second relates to the organizational structure that can foster the development of an environment in which fraud has a good chance of success. In this regard, in the cases that were uncovered, it was found that these were environments characterized by irresponsible and ineffective leadership. This was possible because the highest corporate level was directly involved. The corporate governance attributes that characterize these illegal situations are aggression, arrogance, cohesion, loyalty, blind trust, ineffective controls, and gamesmanship. The first two concern attitudes and motivations of managers who want to be the leaders in that type of business or even exceed the earnings expectations formulated by analysts. Cohesion, loyalty, and gamesmanship increase the likelihood of not looking at the books, of not sensing the warning signs. These combined with blind self-confidence and ineffective controls can undermine the work of internal controllers themselves and block their role in preventing and detecting fraud. In sports this has been found in those cases that have been referred to as “state doping,” but this has also involved the omertà and connivance that have been highlighted within specific sports circles.

The third category concerns the manager’s decision-making process and intentionality in implementing the fraud. The choice is between properly and ethically pursuing business objectives and instead using illegal strategies to blow the company’s stability and growth out of proportion. Management can be urged to exercise illegal actions in the presence of certain favorable conditions concerning:

- Personal financial advantage – management’s gain is linked to company performance through profit sharing, stock compensation or other forms of benefits.

- Willingness to take risks – desire to make decisions that may also involve criminal or civil risks.

- The opportunity to defraud – corporate organization is such that it seems possible to activate financial fraud procedures.

- Pressure from third parties – pressure is exerted internally and externally to the organization in order to maximize shareholder value.

- Ineffective controls-the chances of getting caught are very low

Purely in sports, the intentionality of the athlete to want to use illicit substances to improve his or her athletic performance plays an essential role. Money, fame and success are at the root of this kind of fraud, and if you add to that the ineffectiveness of controls and pressure from third parties … it is really hard to resist.

My work knows no vacations, there is no time of the year when sports and competitions stop. In the next few weeks there are the European table tennis championships, at the same time, the Italian sailing championships, while the girls’ tennis continue their tournaments and will now travel to North America. This is to talk about some of the sports I am involved in. It is a job that requires a strong dedication and interest in the lives of these athletes. It is work that is mostly done remotely. It is an almost daily commitment during competitions. These are collaborations that can last for years but also for a few months, especially when the families or the athletes/athletes bear the financial burden.

It’s a job, unfortunately, today based very much on the athletes’ stories, because it’s very rare to attend competitions. Before covid when I worked a lot with shooting with Italian athletes and foreign nationals the work is almost always in attendance, I would go to the most important competitions and you would live the experience with the team, being able to intervene at the precise moment when the need arose and to implement the mental routines pray.

Still, it remains a very interesting and helpful job. In particular, in recent years I have seen the great educational value that the sports psychologist can play with adolescent boys and girls 14 years old and up. They know nothing about how to approach competitions, the value of mistakes, how to learn, and more generally the rules of sports. No one teaches them these things while there is only an emphasis on physical fitness and technique, aspects that are obviously necessary but not sufficient to know how to compete and grow as a person.

If these aspects are missing, competitive sports at this age can be a source of insecurity. Sport is a school of life only if it teaches how to cope with difficulties and overcome obstacles, in this way developing the young person’s personality. Otherwise it will only be a form of technical expression without a soul.

Global Changes in Child and Adolescent Physical Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

This meta-analysis provides timely estimates of changes in child and adolescent physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. By pooling estimates across 22 studies from a range of global settings that included 14 216 participants, we demonstrated that the duration of engagement in total daily physical activity decreased by 20%, irrespective of prepandemic baseline levels. Through moderation analysis, we showed that this reduction was larger for physical activity at higher intensities. Specifically, the average reduction in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day during COVID-19 (17 minutes) represents a reduction of almost one-third of the daily dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity recommended for young children (~3-5 years) and school-going children and adolescents (~5-18 years) to promote good physical health and psychosocial functioning.

We found that longer durations between pre- and post-assessment were associated with larger reductions in physical activity. It is possible that the cumulative toll of the pandemic has compounded over time to negatively affect children and adolescents,63 including their levels of physical activity. This aligns with a recent meta-analysis on youth mental health,18 which found that the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms increased across time during the pandemic. The temporal aspect of our findings is also broadly in line with research on the psychology of habit,64,65 which suggests that habits are contingent on the types of stability cues that have been significantly disrupted during the pandemic. Most of the known multicomponent, family, social, and community support mechanisms of child and adolescent physical activity66 were unavailable during COVID-19. This undoubtedly created a “perfect storm” for habit discontinuity65 in the context of child and adolescent physical activity.67 Research has also shown that young children with consistent access and permission to use outdoor spaces during COVID-19 had better physical activity outcomes.50 These children exhibited smaller reductions in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and were approximately 2 times more likely to meet physical activity guidelines during COVID-19. Taken together, changes in restrictions and the unpredictability of access to typical physical activity outlets for children and adolescents have likely contributed to changes in their physical activity levels and to greater engagement in displacement activities (eg, screen time12) that risk promoting an increasingly sedentary “new normal.”68

We found that reductions in physical activity during the pandemic were larger for samples at higher latitudes, corresponding to regions of the globe where restrictions coincided with a seasonal transition into the summer months. This finding is consistent with prepandemic data showing that unstructured summer days during school holidays can have negative associations with both academic and physical health behaviors,69-71 often referred to as the “summer slide.”72 A recent estimate of such a summertime reduction of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity of 11.4 minutes69 is substantially lower (~ 50%) than the pooled estimate from our meta-analysis, however. This suggests a substantial intensification during the pandemic of the usual summer slide into physical inactivity,70 which warrants particular attention from policy makers seeking to help children “sit less and play more,”73 as targeted initiatives will be needed as children emerge into the summer months.

There is an urgent need for public health initiatives to revive young people’s interest in, and support their demand for, physical activity during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. In terms of practice implications, research on physical activity promotion and maintenance during childhood consistently shows that multicomponent, multimodal, and multioutcome interventions work best.7,66 Therefore, public health campaigns can have greater effect if they are child-centered, target a variety of physical activity modalities, and incorporate the family unit and wider community as co-constructors of lasting physical activity behavior change.

I want to be repetitive by saying that, in Italy, probably one of the primary causes of the reduced recognition and affirmation of the professional role of the sport psychologist is the psychologists themselves.

This weekend the master’s program we organized in Milan ends, and the participants presented the project work of their internship period. Well in some sports clubs a psychologist was already present or had worked in the recent past. In one swimming club the colleague had left a totally negative perception of himself, in another as many as two psychologists had taken turns and never completed the work because after a few months they had left, in another case the psychologist only did online interventions, in another he was a relative of the president and was never on the field, and in yet another he only took care of the competitive team but did nothing with the younger ones.

Now in all these situations the Master’s psychologists intervened, and thanks instead to their effective counseling approach they managed to convey another perception of our profession and were ultimately appreciated for the work they did. Of course they had the supervision of Daniela Sepio and myself and were provided with appropriate tools but the success factor was their professional willingness to get in touch with the sports environment to understand its needs and formulate possible responses.

On the other hand, I regret that many colleagues lack this sensitivity and the enthusiasm necessary to understand that without proper training they will never be able to pursue this profession. I also regret that those who organize master’s degrees in psychology do not understand that only through internships, as is the case in every profession, can one really test oneself and how much one is learning.

I also wonder if this might not be due to the fact that many master’s degree directors, themselves, have had only a reduced experience in the counseling world and often limited to one age group or only one sport.

Those who would like to know more can contact me.

Sport has changed dramatically in the last 40 years and I believe that its different organization has greatly influenced the motivation and personality development of young people.

Once upon a time it was the young people who organized themselves and this approach stimulated them to take on responsibilities regarding the choice of the game, its rules, refereeing and choice of teammates. Today, most of these issues do not affect them because they play only in organized structures led by adults. Obviously, sport will not go back to an organization run by young people, but what skills this way of playing sport developed and how the same kind of skills can be developed today.

Today: Kids only play and participate in sports when adults formally organize them. The rest of the time they play video versions of sports on Playstations. You rarely see children organizing informal, real-world games on their own.

40 years ago: Children of all ages went to play in the backyard, at the oratory, or on a vacant lot near their homes.

Today: Children play on perfectly manicured and lined fields.

40 years ago: Children played against other neighborhood children of all ages and had to improve to compete with the older kids. They often played alone or with each other, throwing a ball against a brick wall to get better.

Today: Children attend dedicated sports facilities where an instructor teaches them only one sport. They attend different summer camps.

40 years ago: Children chose their teams by picking the best first and then the others.

Today: The team is made up of the coach.

40 years ago: Kids made up their own rules to fit the place they played.

40 years ago: You had to develop leadership skills to influence who was on your team, receive passes and be recognized as one to have on the team. Today: Adults make the decisions in youth sports: they choose the teams and how to play.