The 8° year of the “Football Together” project is coming to the end. It is a complex project aimed at young people with intellectual disabilities, with special reference to young people with autism. It is a long time in which many of the participants have gone from being teenagers with autism to young adults.

It is a project of AS Roma in collaboration with the Academy of Integrated Football, which aims to promote an innovative methodology of soccer training among these young people, starting from the age of school soccer 6-12 years old to the more game-centered activity in later ages from 13 years old and beyond.

474 youth have been involved in 8 years - Each year the number of youth with intellectual disabilities has increased. Initially the project covered the soccer school age groups, going forward it was enriched by the upper age group we called “Cub Scouts Grow Up,” which now includes youth who have reached the age of majority.

80 are the youth with autism involved in the 2022-23 activity - Currently, the youth are divided into three groups according to age and their motor and psychological skills. The group composed of youth with a severe level of autism are each followed by a single professional (instructor or psychologist). The group of younger youth (6-9) years old and with an average level of functioning carry out group activities and ball games. The group of adolescents over14 of medium to high functioning follow a soccer training program and play soccer games5 among themselves, in an integrated way with players from the AS Roma soccer school and participate in events organized by other clubs or FIGC.

30 were the young people with autism in the first year - Calcio Insieme began in September 2015 with the collaboration of some schools in Rome that promoted among the families of pupils with intellectual disabilities the knowledge of this initiative, organized informational meetings with the staff of Calcio Insieme to begin to build a Community on the territory in which school, family, promoting sports subjects, and staff could feel part of a common project at the center of which are children with intellectual disabilities and in particular those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

28 hours of staff training - In 2015 the staff participated in a 28-hour Training Course by “Football Together” prior to the start of the activity, which had experts in the various fields of intellectual disability as lecturers and speeches by parents, school workers, and sports clubs. At the beginning of each year the staff is involved in a refresher training.

24 are the practitioners - The staff consists of 10 soccer instructors, 6 sports psychologists, 1logopedist, 3 doctors, 1 school and parent relations manager,1 technical area manager, 1 scientific manager and 1 institutional relations manager.

20 are the schools involved - The young people with intellectual disabilities involved come from 20 schools in the Roman area. A collaborative relationship has been established with each of these schools through the principal, support teacher and families.

9 are the videos to talk about Football Together - 6 short educational videos each lasting a few minutes were made, funded by the presidency of the Lazio Region. 3 more videos were made to present the activity carried out and the results achieved.

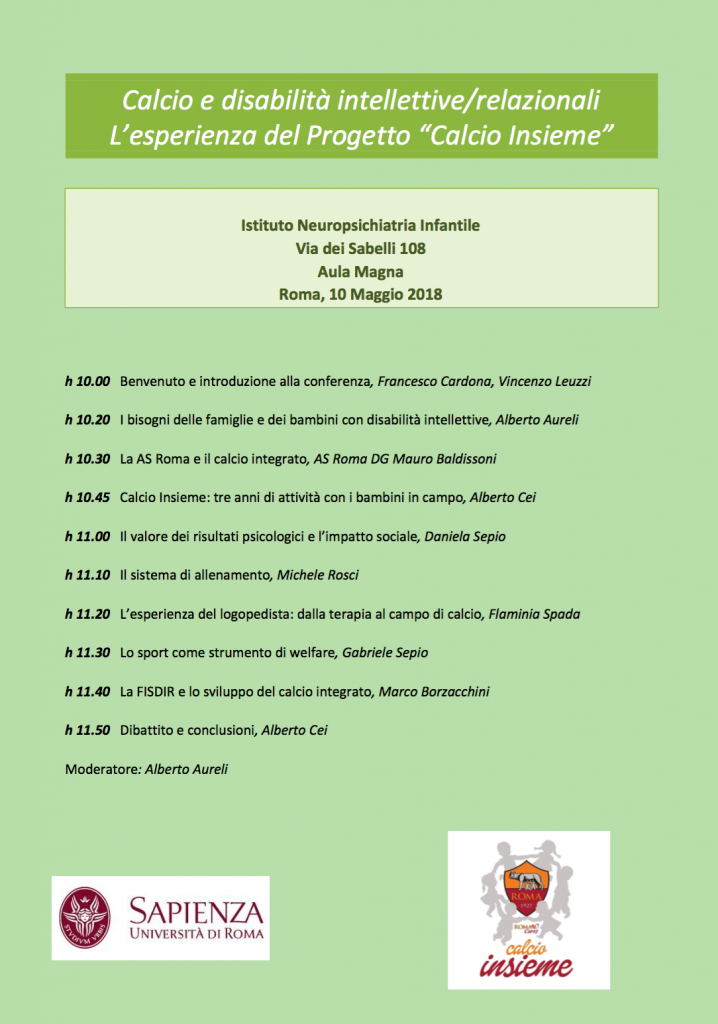

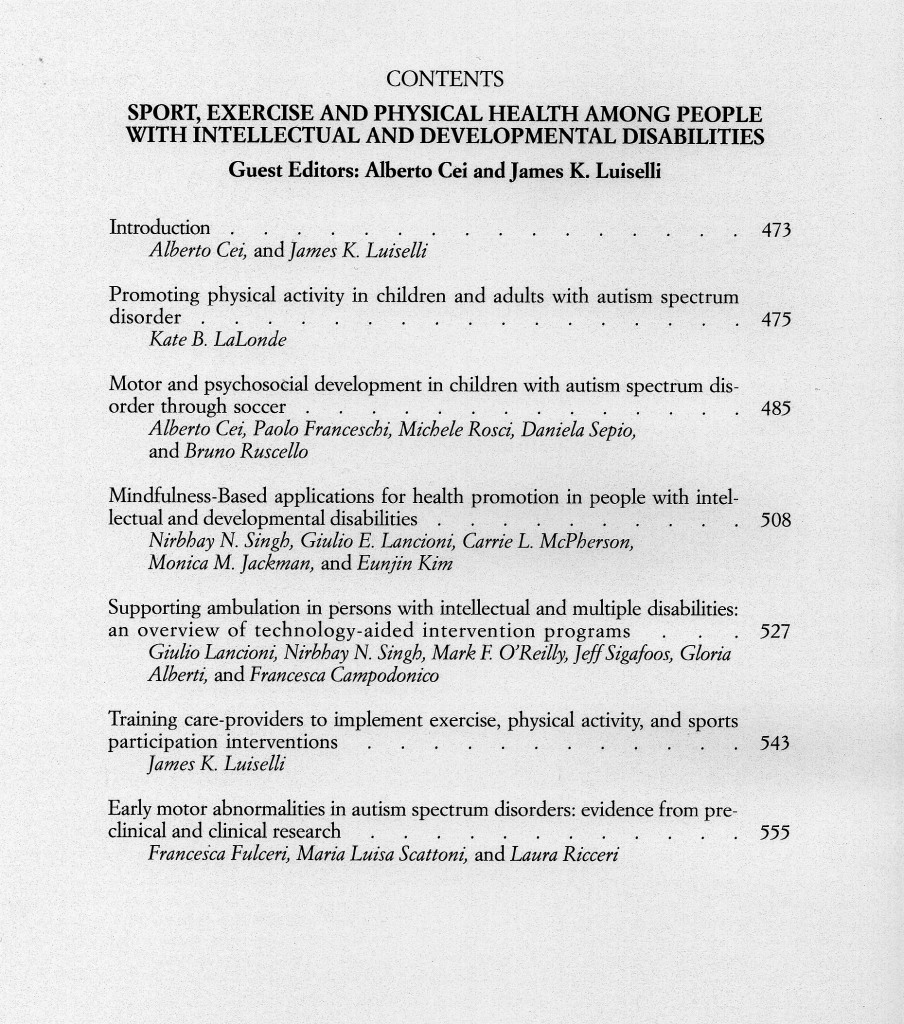

7 are the scientific contributions published - 3 are the scientific articles published in international journals. A special issue of the journal “Movement” and an article in the journal of the School of Sport were published. During Covid the activity carried out online with these young people produced a technical book of exercises to be done at home. The activity was presented at the national conference of the Italian Dyspraxia Society, at a seminar held at the Institute of Neuropsychiatry at Sapienza University in Rome, and is an integral part of the Level IV Course for Coaches organized by the School of Sport in Rome.

3 are the summer camps - Summer camps were held to: respond to the needs expressed by families with children with intellectual disabilities, offering weeks of summer camp, free of charge; create a model of summer camp and typical day, based on movement, declined in the different playful-motor and sports expressions; constitute a concrete model of integration thanks to the presence at the summer camp also of siblings or classmates, their peers with typical development. Each week of camp was spread over 5 days for a total of 25 hours per week.

3 are the young people who served as assistant instructors - These young people have turned 18 and have been with us for a number of years, their passion for soccer is well-rounded. They have served as assistant instructors during summer camp weeks. In the future they could put their acquired sports skills to use and make sports their career field, but their intellectual disability is an obstacle. The goal is to break down this obstacle and build an educational pathway to make soccer accessible to these girls and boys also as a possible career field.

2 are the areas investigated: motor-sportive and psycho-social - Different motor-sportive tests were proposed and experimented with before arriving at the final one that uses a 5-level behavioral description of basic motor skills, repeated twice a year, at the beginning of the educational journey and at its end. During interviews with parents, they were asked to fill out behavior fact sheets at the beginning and end of the year to assess their perception of improvement on the psychological and social areas investigated. Similar psychological assessments were conducted by the psychologists of these young people, also examining in the more serious youth the duration of their active engagement during each training session.