Monthly Archive for March, 2023

In the previous blog, I talked about the need to develop in young athletes awareness in their skills and how to compete. The article below, in this regard, discusses how coaches should be “landscape designers” to provide their students with the best environment in which to discover and practice their motor and sports skills. The name of this approach is: Nonlinear Pedagogy

Chow Jia Yi, Komar John, Seifert Ludovic. The Role of Nonlinear Pedagogy in Supporting the Design of Modified Games in Junior Sports

Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2021.

In their paper, Woods et al. (2020) described howsports practitioners are seen as “landscape designers” who cansupport learners to find their own way in learning movementskills by perceiving and navigating through emergentperformance-related problems. This would indicate that thelearner is not a passive actor in the journey of acquiring andadapting skills. Athletes and, in the context of this paper, juniorathletes would learn through involvement in practices andperformance environments that challenge them to be problemsolvers in a self-regulated manner. What do these athletes learnfrom a “wayfinding” analogy? Woods and colleagues arguethat through wayfinding, learners can deepen their knowledgeof the environment (also see Sullivan et al., 2021 discussionon this) by being exposed to a continuum of affordances inthe environment as the wayfinding process is one that ischaracterized by embodiment and embedment (i.e., notdecoupling the emergence of movement.

The opportunity is for the young learners to acquire a range of movements that could be transferred to other similar movement contexts. Importantly, it is also about “learning to learn” (Hacques et al., 2021). Individuals learn to make decision, learn to explore, and learn to adapt, and all these can take place over a longer time scale (Hacques et al., 2021).

We want these young athletes to be provided with opportunities to achieve adaptability (i.e., flexibility and stability) in the way they use their repertoire of movement skills in performance contexts.

On the other hand, with multi-sports, the learner would be exposed to a greater range of movement possibilities through the attunement to various informational sources present across different sports contexts. For such involvement in multi-sports, it can potentially expand the repertoire of movement solutions available to the learner where greater adaptable movements (maybe even atypical ones!) can be effective in the target sports subsequently. This is where innovative, spontaneous, and individualized movement solutions become a valuable asset to the individual who has been exposed to a wide variety of sports.

Nonlinear Pedagogy advocates practice contexts that incorporates situations that challenges the learner to “replicate” the movement skill in different and dynamic contexts since many of these more representative “practices” will never challenge the learner in exactly the same way (i.e., the idea of repetition without repetition).

Working with young adolescents in different sports from tennis to soccer, fencing to shooting or golf, I realize more and more that as early as 14 years old, boys and girls have developed a totally biomechanical idea of sport. So I am good when I execute you technically well what I can do for the duration of the competition. They interpret, on the other hand, competing poorly is explained as having failed today to do what I can do. The cause is that the technical execution was not coming well, or it is about the opponent or anxiety and fear of making a mistake. The solution for the next competition, almost always, is to improve technique and be more focused and less emotional.

Improving technically depends on what the coach will do about it. Improving mentally consists of telling oneself that one should not get down or angry, while both should be calmer. Usually the psychological explanation is secondary to the technical one. One gets angry, in fact, because the technical action does not come out well or because the opponent was lucky or better.

This approach, highlights that the mental component is only a logical reaction to something technical. This explains phrases such as:

- “It’s not me playing badly, it’s that the other guy was only making winners.”

- “It’s not me, it’s that the forehand didn’t fit today.”

- “It’s not me, it’s that he took a lot of nets”

- “It’s not me, it’s that it was the wrong stick”

- “It’s not me, it’s that suddenly the clouds changed the light”

- “It’s not me, it’s that the ball could not be kicked from that position”

These athletes until they train differently will never improve.

At the Vivicittà press conference held at a scientific high school in Rome, a student asked how important the climate in a sports group was to sustain interest in sports.

I replied that others whether they are parents, coaches, managers or teammates are crucial because no one learns alone. We all need an environment where we feel appreciated for what we do. Psychologists say that everyone can be successful, meaning by this statement certainly not those who win a race. They mean that everyone can learn, improving through their efforts.

Consequently, those who organize sports must build a climate in sports clubs that fosters engagement and learning. Sport is flexible; everyone can learn regardless of their starting base. Sport itself is inclusive because it bends to everyone’s needs; it is up to those who promote it not to build barriers that prevent someone from participating.

So we can all be athletes for life.

“In Italy no child plays in the street anymore. We used to play 3-4 hours in the street and then go to training, today this doesn’t happen anymore. It’s not by chance that players are still born in those countries, like Uruguay, Argentina or Brazil, where they still play a lot in the street.” Italian coach Roberto Mancini about the difficulties of Italian soccer in developing talent in recent years.

One cannot but agree with Mancini. I myself, who never played for a team, used to play 2 hours every day of soccer, in the backyard, in a park near home, or at the oratory. All this until the end of junior high school was absolutely common, in the free time that was a lot you played ball, even just headers on the landing, without making the ball down the stairs or inside the elevator pit.

One learns little by doing an activity even three times a week for two hours. Does one learn Italian by studying it for this same length of time? Of course not, any teacher would answer. The same is also true for soccer, if one did not consider it as a sub-activity that one can learn instead by devoting little time to it. You learn Italian because you speak it every day outside of school and then teachers teach you how to use it properly. English, for example, is not learned for precisely the same reason that soccer is not learned and that is because it is not practiced outside the few hours devoted to it in school.

A second important point is that the game of football practiced in a self-directed way develops skills precisely because of the self-organization that children give themselves. In fact, it stimulates,

- the ability to adapt to the ground where they play, to ever-changing widths and lengths,

- the creativity of young people to find solutions

- the acceptance of others, otherwise one is excluded,

- cooperation among teammates, there is no approval towards those who never pass the ball,

- motor coordination, to overcome the irregularities of the field.

It is quite evident that such self-coached young people find it easier to be taught to play soccer.

Every person, in his or her daily life, tries to predict what may happen to him or her so that he or she can lead an organized life that develops in the expected way.

The same is done by the athlete who studies the opponent’s moves in order to be able to challenge him, or in sports influenced by weather conditions, they research the information they need to know what the weather situations they will encounter during the race will be.

However, we are all aware that although forecasts make it possible to know how likely what is predicted should happen, there is always at the same time a large margin of unpredictability, which can challenge the forecasts.

Therefore. unpredictability is as much a part of our lives as that of athletes. How many times has it happened that a team or an athlete would take a game as easy and, instead, lose it because they did not predict that the opponents could play so well. How many times have we heard a coach say, “We did not expect that kind of play, which put us in trouble from the start.”

On the contrary, we must be aware that the unexpected are there, and precisely because they are not predictable, we do not know when they will occur.

To the athletes and female athletes I work with, I always tell them that in every race there will be a moment when they will be in trouble and that they most likely did not foresee. That is the most important moment in the race because the competitive stress will increase, they will wonder what is happening differently, maybe they will be amazed because until a moment before everything was fine. These are the moments that differentiate experienced athletes from others. The former know that they have to reason and find a solution while the others panic and start making many mistakes.

An easy way to start learning how to handle these critical phases is to train yourself to imagine what could go wrong in a race and commit to finding a solution quickly. This strategy trains the mind to respond proactively to unforeseen events; in this way, one builds a mental file, classified management of unforeseen events, in which to place those that actually happened and those merely imagined with their solutions.

ISSP MASTER CLASS SERIES – LECTURE #2

EXCELLENCE IN WORKING WITH OLYMPIC ATHLETES AND COACHES: TWO CASES FROM CHINA AND DENMARK

New Date: Thursday, May 11th, 2023

Speaker: Prof. Gangyan Si and Prof. Kristoffer Henriksen

Title: Excellence in working with Olympic Athletes and Coaches: two cases from China and Denmark

Length of Session: 75 minutes (45-minute lecture, 30-minute Q&A)

Time: 12:00 UTC (Chicago 7:00, Sao Paulo 9:00, London 13:00, Beijing 20:00, Tokyo 21:00)

Where: Zoom

Register: https://issponline.org/webinar-registration/

Program Overview

Recent sport psychology literature highlights the importance of developing and implementing service delivery practices grounded in the cultural and contextual frameworks within which practitioners and their clients perform. Two successful examples of excellence in delivering contextually grounded practice are represented in the work of Prof. Gangyan Si and Prof. Kristoffer Henriksen and with elite coaches and athletes. Gangyan is a sport psychologist for Team China, an Asian international sports superpower. Gangyan will present what he experienced and learned working with top Chinese athletes and coaches during the past five Olympics Games. Kristoffer has been a sport psychologist for Team Denmark since 2008. Located in Western Europe, despite being one of the smallest countries in the world, Denmark has experienced great success at the international level. Kristoffer will present what he experienced and learned while supporting Danish athletes and coaches on-site during the London, Rio, and Tokyo Olympic Games. In this Master Class, Gangyan and Kristoffer will share stories, insights, and reflections from their work, while offering insight into differences and similarities in their work and how they are rooted in different cultures and contexts as well as personal preferences.

About The Speaker

Gangyan Si is a senior sport psychologist at the Hong Kong Sports Institute and a professor at the Wuhan Sports University in China. Gangyan is a certified psychologist and has been appointed as an expert by the Chinese Olympic Committee for providing psychological services for the 2004, 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020 Olympic Games for different Chinese Olympic teams. Over the years, Gangyan has also worked directly with different Hong Kong teams providing sport psychology services and traveling with the teams for Olympic Games, Asian Games, and World Championships. Gangyan’sresearch interests include applied sport psychology service, cultural sport psychology, and athlete mental health and mindfulness training.

Kristoffer Henriksen is a professor at the Institute of Sport Science and Clinical Biomechanics at the University of Southern Denmark. Kristoffer’s research in sport psychology takes a holistic approach and explores the social relations among athletes and how they influence development and performance, with an emphasis on successful talent development environments. He also acts as a sport psychology practitioner in Team Denmark (a national elite sports institution). In this role, Kristoffer focuses on developing mentally strong athletes, coaches, and high-performance cultures within Denmark’s national teams. Kristoffer has supported athletes at numerous championships and three Olympic Games.

Program Format

Attendees can participate in an ISSP Master Class session right from their office or home. Registrants will be provided the Zoom link upon registration to access the presentation right on the web in real time. If you are unable to watch the session live, a recording will be provided afterward to all registrants.

It started in 1983 promoted by UISP and has not stopped since. The “greatest race in the world” continues to be the great protagonist of sports for all, embracing in a single, original formula, professional athletes and Sunday sportsmen with the competitive 10km in addition to the recreational motor walk in many Italian and foreign cities, departure for all at the same time, single ranking based on compensated times. And every year, a theme to fight for: peace, human rights, environmental respect, social equality, solidarity among peoples. So that freedom (to run) is not a privilege of the few.

Let us then follow together some of the most significant stages:

1984 - “Italy, ready, go!”: after the prologue in Perugia in 1983, the Vivicittà adventure starts. 30 thousand people run simultaneously in twenty Italian cities to defend the historic centers. In the Rome trial, the overall winners, both Russians, Vladimir Kotov and 26-year-old Palina Gregorenko, impose themselves.

1986 - Vivicittà lands in New York launching a message of friendship and solidarity among people. Participants grow to 60,000. The route is reduced to 12 km to standardize the courses and make the compensated rankings more truthful. The overall winners are running in Rome: Britain’s Tim Hutchings and Italy’s Anna Villani.

1989 - Vivicittà runs with a mask. A system to detect pollution levels during physical activity is tested in Rome by having some athletes run with a special mask. On the occasion of the European Year for Combating Cancer, a vademecum of rules for prevention is distributed to all participants. 80 thousand athletes run in the 33 Italian and 7 foreign venues. Salvatore Antibo wins over all, winning for the second consecutive time in Palermo.

1990 - after the fall of the wall, the event is in reunified Berlin. Record number of cities entered: 34 in Italy and 7 abroad: in addition to Berlin, Seville, Barcelona, New York, Budapest, Lisbon, Brussels. The winner runs in Siena and is Rwandan Ntawulikura while the German capital gives the female winner, Uta Pipping.

2000 - “With everyone’s reasons for everyone’s rights” is the message accompanying Vivicittà in its debut in Baghdad. Roman marathon runner Giuseppe Papaluca walks the 1,000 km from Amman to Baghdad to bring a message of peace. Catania reintroduces compensated winners with Kenyan Robert Kipchumba and Italian Agata Balsamo.

2008 - two more iconic cities united by Vivicittà’s message. Running in Beirut and Bucharest in the name of tolerance and integration. 70 thousand athletes participate in the 40 Italian cities. Victory goes to Kenyan Philemon Kipketer Serem and Italian Renate Rungger.

2011 - runs in the name of 150 years of the Unification of Italy. 100 thousand runners at the start in 38 Italian cities and 16 around the world. Vivicittà also involves 17 penitentiary and juvenile institutions and the Palestinian camps in Lebanon, as the concluding event of the Palestiniadi. Among the winners, absolute primacy to Africans with Moroccans Khalid Ghallab among men and Hafida Izem among women.

2016 - #Freetomove, the theme of Vivicittà 2016 was related to welcoming and the social value of sport, which manages to overcome geographical and social borders. The symbolic place of this edition – which saw 60,000 participants in 43 Italian cities and 11 in the world – was Lampedusa.

2022 - after a two-year stop caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, Vivicittà returns throughout Italy, with a special dedication to Peace. Vivicittà – the race for peace, gathers 20,000 participants in 30 Italian cities.

Roberto Mancini and Luca Marchegiani told the truth, the situation in Italian soccer is desperate. It is a situation without solutions if one is forced to summon foreign athletes de facto, as they have trained and play abroad but with Italian passports.

The alternative is to summon youngsters who play in leagues lower than Serie A, so as Marchegiani points out the concept of merit is lacking, in fact “the national team was a point of arrival, now Mancini has to call up rookies.”

The problems to talk about would be too many and I get a headache just thinking about them. One out of all of them that has not been talked about concerns the issue of what interest foreign ownership of teams has in promoting Italian players when you can win by having 11 foreigners on the field as well. In Serie A alone there are as many as 7 foreign owners, accounting for 35% of the total. In Europe, only in Germany is there not this phenomenon, which in the Premiere League has reached 75% of ownership.

We are witnessing a clash of different cultures, where those with economic power will win. There is no more time for the discovery and formation of the heritage represented by young people playing soccer, interest has shifted only to the result of the teams, which in turn is independent of the function of the youth sector. Those with economic power can choose players for their teams all over the world, why should they pay attention to a narrower market?

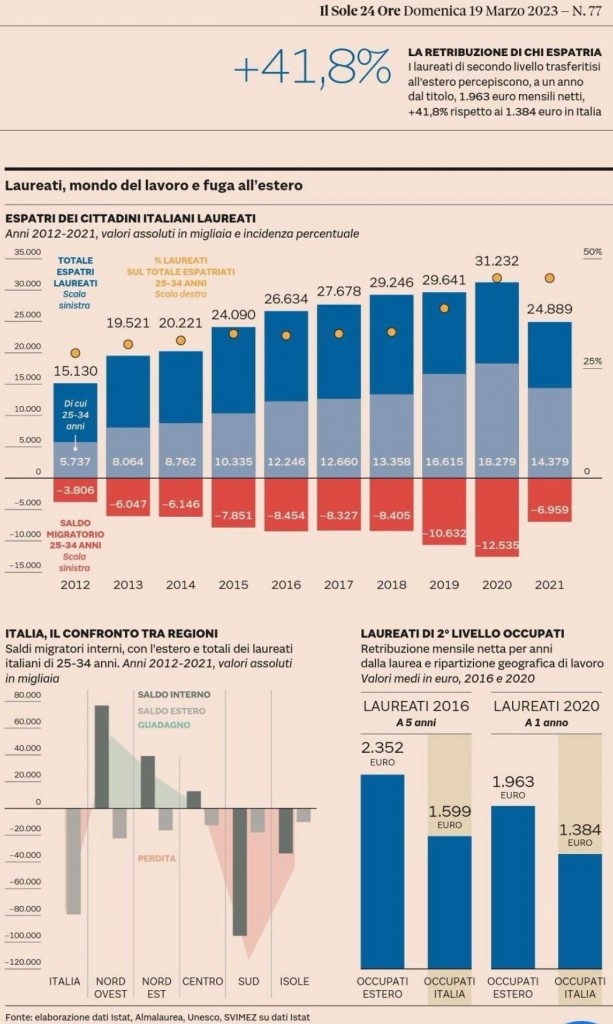

- One million Italians expatriated between 2012 and 2021. 250,000 were graduated.

- In 2012, 5 percent of all college graduates left, then up to 8.9 percent in 2018 and down again to 6.7 percent in 2021. Almost two points higher, then, than ten years ago.

- Italian graduates who emigrated abroad earn 41.8 percent more a year after graduation than those who stayed in Italy.

- The North compensates for the exits by attracting young people from the South; the South is stuck with the dry loss of talent. A double wave that tests the resilience of the entire country.

- The “university desertification of the South” is taking place, points out economist Gaetano Vecchione: “In 2041 the South will lose 27 percent of enrollment, the Center-North about 20 percent. Between denatality, low school-to-university transition rates and migration in 2021, the gap between North-Center and South marked a difference of 80 thousand matriculated students. In the past 20 years, about 1.2 million young people have left the Mezzogiorno, 1 in 4 are college graduates. In 2020 alone there were 67 thousand and the share of graduates rose to 40 percent.” (Fonte: Sole 24 Ore)