Pandemia has changed the way we work and maintain social relationships, it has been, so far, 10 months where we have trained ourselves to change maybe even initially against our will.

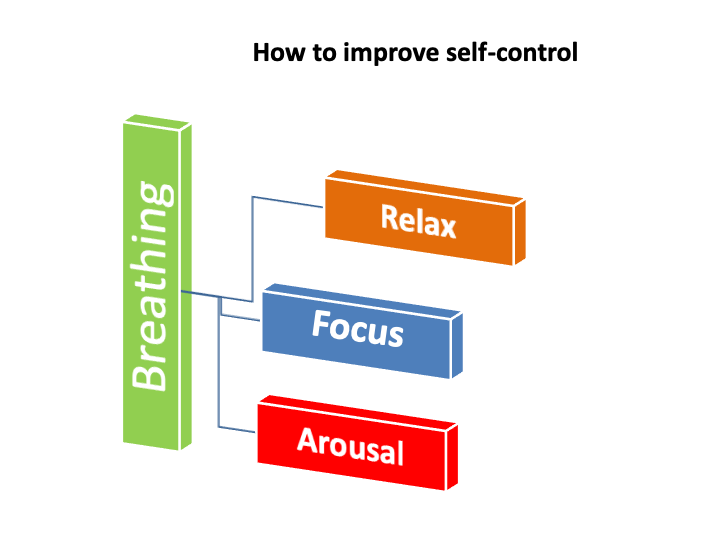

My work is currently only online. I’m on WhatsApp on some days even for 5/6 hours, meetings with colleagues and international conferences are only on Zoom, I made short videos of a few minutes to teach specific breathing techniques and concentration training. Lessons and university exams only on the platforms provided.

I carry out a professional activity requiring direct contact with people, while in these months it has happened almost exclusively through smartphones and pc. What are the costs and benefits of this approach? Certainly it requires a better organization of work and a greater investment of time. This happens because if you are not in contact with the athletes during training, you don’t have the ongoing relationship that comes from being present at competitions and training. There is no longer the possibility to interact with them and the coaches in an informal way and in presence on the field.

Instead, to be able to interact, specific moments had to be scheduled, generally after lunch or after afternoon training. In addition, for some of the exercises I proposed, I made videos of no more than two minutes, sent via smartphone, that constituted real tutorials on a topic of psychological interest. This kind of communication represented a further element of novelty for me, whose usefulness I nevertheless experienced, since the athletes had instructions on video to review according to their needs.

The costs concern the impossibility of carrying out interventions in the here and now, that is, on events that have just happened, but we always work on the report of athletes and coaches. Another limitation relates to the absence of the psychologist from the interpersonal dynamics between coach and athlete during training and the extremes of their interactions on factors almost exclusively technical and tactical and physical improvement, which on the other hand are the purpose of the work of coaches and physical trainers. The accentuation of attention on these factors can lead in some cases to give less importance to the mental component of training, putting in the background the awareness that it is the mental attitude (i.e. how one lives training) that determines the quality of the sport and motor commitment and its success.

We will see in the coming months how we will emerge from the pandemia and how our work will be changed. My feeling is that it has changed a lot and that digital will become a significant aspect of the psychologist’s work as well.